Possibly the most relaxed and comfortable small-boat sailor we've seen. The sailor is lying down in a Laïta pram dinghy designed by François Vivier of www.vivierboats.com. The little sister of his popular Seil 18, the Laïta is 12 feet long by 4 ft 7 in wide, 165 lbs and takes one or two. Available as plans, a kit or a completed boat.

See previous pages for:

• Sailing dinghies

• Rowing boats

• Rowing-sailing boats

• Sailing canoes

Pacific outrigger canoes

New for me ... I'm currently (2022) building a 5.4 metre Opelu-type fishing canoe.

Follow the building process ... and the paddling process ... on the "Va'a on Mull" Facebook page.

These were the fishing and voyaging craft of Polynesian peoples right across the Pacific islands. They have a long, very slim main hull, stabilized by an even slimmer outrigged hull (ama) parallel to the main hull but 3 feet or more off to the side. The main hull of a traditional outrigger canoe has much higher sides than a sea kayak so the crew sits higher above the water and gets a fairly dry ride.

These were the fishing and voyaging craft of Polynesian peoples right across the Pacific islands. They have a long, very slim main hull, stabilized by an even slimmer outrigged hull (ama) parallel to the main hull but 3 feet or more off to the side. The main hull of a traditional outrigger canoe has much higher sides than a sea kayak so the crew sits higher above the water and gets a fairly dry ride.

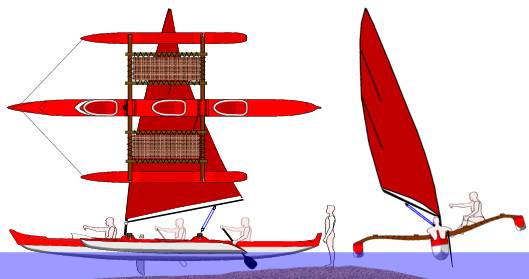

To find out more about traditional canoeing, you could get a copy of The Hawaiian Canoe (Tommy Holmes, Editions Ltd, 1981 and 1993). This is beautifully illustrated, covers the history and culture of leisure, racing and surf use of Hawaiian canoes, and is well worth a read whether or not you want a canoe yourself. The image above right is from a diagram in the book and shows a wide canoe made from a single tree, about 42 feet long with seats for six. It has a traditional crab claw sailing rig.

Outrigger canoes can all be paddled, using long single-blade paddles.

Tommy Holmes' world of cruising, surfing, fishing and the occasional race has largely given way to a "go hard or go home" approach with very fast, skinny, wet, lightweight, high-tech boats that can't be sailed and are intended for sprint or marathon racing. These boats (not illustrated) are like flatwater racing kayaks except that the paddler sits on them rather than in them. A one-person racing canoe may be 21 feet long but weigh as little as 26 lbs thanks to the use of exotic materials such as vacuum-bagged carbon fiber in epoxy resin. The ama may be tiny because a skilled racer relies on balance, keeping the ama up in the air as much as possible.

Outrigger canoes are manufactured in fiberglass in sizes suitable mainly for one, three or six paddlers. One-person outrigger canoes are often designated OC-1, three-person canoes are called OC-3, etc. There is an active club racing scene in Hawaii, in Tahiti where they are called va'a, in New Zealand where they are called waka ama, and California. There are some outrigger canoes in Europe, but no major racing or sailing scene yet.

Outrigger canoes are manufactured in fiberglass in sizes suitable mainly for one, three or six paddlers. One-person outrigger canoes are often designated OC-1, three-person canoes are called OC-3, etc. There is an active club racing scene in Hawaii, in Tahiti where they are called va'a, in New Zealand where they are called waka ama, and California. There are some outrigger canoes in Europe, but no major racing or sailing scene yet.

Traditional canoes intended for sailing, fishing and paddling on the open sea are more substantial and heavier, with higher sides to shelter the paddlers from waves and spray. For example, the six-person canoe above or the two-person Ulua, which is a handsome 17 ft 8 in beach cruiser by Gary Dierking. The yellow canoe above left is a sketch of Ulua. Gary has an excellent and beautifully-illustrated website here and he's the author of an excellent book, Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes : Modern Construction Methods for three fast, beautiful boats (International Marine, 2008).

16 ft 8 in is about the minimum length that will give good looks and reasonable performance in a two- to three-person recreational paddling canoe with overhanging ends like this orange one.

16 ft 8 in is about the minimum length that will give good looks and reasonable performance in a two- to three-person recreational paddling canoe with overhanging ends like this orange one.

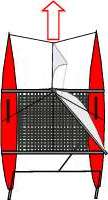

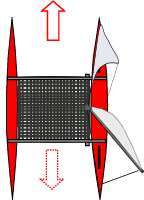

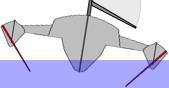

An OC-3 for leisure use can be anything up to about 33 feet long. They make fast and seaworthy sailing boats if you add a mast and a small sail, and maybe a second outrigger to turn them into slim trimarans, steered with a side-mounted rudder or with a paddle like the red boat shown below.

Outrigger canoes are beautiful and exciting. Check out the OC-3s at www.holopunicanoes.com. The catch is that for seaworthiness and speed they are 30 feet long.

The normal rules of kayak construction apply if you're building a small outrigger canoe, but you enter a new world if you want to build a 30 foot outrigger. Except on flat water, a long slim hull will break in half unless its construction is heavy, high-tech or both, and that makes it expensive. A big OC-3 must stay well away from rocks but it still needs to be strong. It will sometimes go partly airborne as it crosses a wave, before the bow crashes down into the trough on the other side. For minimum construction requirements see the NKOA safety guidelines at http://s3.wakaama.co.nz/story/1001540/attachments/Waka Ama Guidelines November 2008.doc

The normal rules of kayak construction apply if you're building a small outrigger canoe, but you enter a new world if you want to build a 30 foot outrigger. Except on flat water, a long slim hull will break in half unless its construction is heavy, high-tech or both, and that makes it expensive. A big OC-3 must stay well away from rocks but it still needs to be strong. It will sometimes go partly airborne as it crosses a wave, before the bow crashes down into the trough on the other side. For minimum construction requirements see the NKOA safety guidelines at http://s3.wakaama.co.nz/story/1001540/attachments/Waka Ama Guidelines November 2008.doc

Sailing a canoe 20 or 30 feet long usually takes a crew of three or more. An OC-6 can sail at 20 knots with two of the crew struggling to steer and the others sitting on a trampoline rigged over the water between main hull and ama. After transport to a new location it can take six hours to rig one for sailing, so they're practical for a canoe club which can store its boats next to the water.

Other multihulls for exposed waters

To us, a beach cruiser must be light enough for its crew to carry up the beach, big enough to give them some protection from spray, sun and cold, and have a reasonably efficient sailing rig. It will generally need a short mast that can be taken down at sea. If you want that in one package, you'll probably have to build it yourself.

To us, a beach cruiser must be light enough for its crew to carry up the beach, big enough to give them some protection from spray, sun and cold, and have a reasonably efficient sailing rig. It will generally need a short mast that can be taken down at sea. If you want that in one package, you'll probably have to build it yourself.

On this page we'll just give some basics, with links to sites where you can find out the detail. In particular there are Michael Schacht's great site at www.proafile.com and the proa section of Craig O'Donnell's Cheap Pages. For the nice design on the left, with a crab claw rig for beach cruising, see Kris Seluga's site at www.rclandsailing.com/catamaran. Last time we asked him he did not sell plans but if you ask him nicely he may e-mail you the dimensions.

Multihulls in general are much less popular than small monohull sailboats, except as total speed machines like Hobies, Darts, Hurricanes, Nacras, Prindles, Unicorns, C-Class and so on. Any sailing multihull is faster than a monohull of similar length, but more complex and expensive, and usually too wide to travel on the roof of a vehicle unless dismantled. Dismantling and re-assembly takes quite a long time.

To fit our definition of a boat which is both seaworthy and small, any multihull must be at least 16 ft long or it will give its crew a wet ride and be unable to cope with windy conditions. However if it is much longer than that or fitted with a big, powerful sailing rig, its crew won't be able to carry it up a beach on their own, and that is next to essential for a beach cruiser. It takes some thought to design a multihull which is hard to capsize but (since any small boat can be capsized by wind or by wave action) easy for the crew to right in difficult conditions.

Micro-multihulls can be made as catamarans, trimarans or proas.

Catamarans have two long slim hulls, usually joined by two aluminum tubes (crossbeams) with a trampoline stretched between them for the crew to scramble around on. The mast stands in the middle of the front crossbeam. Hobie makes some very small cats - see www.hobiecat.com - but they still have fairly high masts and they capsize easily sideways or forwards (pitchpoling). There's a sweet video on YouTube of Lorraine Chase getting dunked when a Hobie 16 pitchpoles in perfect sailing weather and a flat sea. It's called "Lorraine Chase takes a suprise dip". In strengthening winds at sea, you may find yourself looking at that tall mast, wishing for a hacksaw and fingering your VHF radio. You may not need the hacksaw. According to Modern Marlinspike Seamanship (William P MacLean, Bobbs-Merrill 1979) "Hobie cats... are very lightly rigged for top performance in light airs. This is appropriate for small lakes and other protected areas where these catamarans are most often sailed. In the Virgin Islands, however, the rig regularly fails. Usually little damage is done and the whole thing can be put back together with a few new stays."

Catamarans have two long slim hulls, usually joined by two aluminum tubes (crossbeams) with a trampoline stretched between them for the crew to scramble around on. The mast stands in the middle of the front crossbeam. Hobie makes some very small cats - see www.hobiecat.com - but they still have fairly high masts and they capsize easily sideways or forwards (pitchpoling). There's a sweet video on YouTube of Lorraine Chase getting dunked when a Hobie 16 pitchpoles in perfect sailing weather and a flat sea. It's called "Lorraine Chase takes a suprise dip". In strengthening winds at sea, you may find yourself looking at that tall mast, wishing for a hacksaw and fingering your VHF radio. You may not need the hacksaw. According to Modern Marlinspike Seamanship (William P MacLean, Bobbs-Merrill 1979) "Hobie cats... are very lightly rigged for top performance in light airs. This is appropriate for small lakes and other protected areas where these catamarans are most often sailed. In the Virgin Islands, however, the rig regularly fails. Usually little damage is done and the whole thing can be put back together with a few new stays."

Trimarans have a central long slim hull, joined by crossbeams to two similar but often shorter hulls, one on each side. The mast stands on the main hull. The shorter hulls keep it upright against the sideways push of the wind in the sail. There are some commercially-available racing trimarans like the Weta, the Ninja and the old Supernova that have powerful sailing rigs and a trampoline so the crew can use their weight far out from the side of the boat, as a counterbalance to the force of the wind. Small cruising tris have smaller sailing rigs. They may not have a trampoline, because the crew always sits in a cockpit in the central hull. Elsewhere we mentioned kayaks stabilized for sailing by the addition of buoyant floats on each side. See Sailing Rigs For Kayaks & Canoes. One French designer has made prototypes of his Windyak, a mini trimaran which is basically a kayak with a sail and outrigged floats. He says it can be paddled without removing the floats. Last time we asked, it was not yet in production. http://frederic.jouffroy.free.fr

Trimarans have a central long slim hull, joined by crossbeams to two similar but often shorter hulls, one on each side. The mast stands on the main hull. The shorter hulls keep it upright against the sideways push of the wind in the sail. There are some commercially-available racing trimarans like the Weta, the Ninja and the old Supernova that have powerful sailing rigs and a trampoline so the crew can use their weight far out from the side of the boat, as a counterbalance to the force of the wind. Small cruising tris have smaller sailing rigs. They may not have a trampoline, because the crew always sits in a cockpit in the central hull. Elsewhere we mentioned kayaks stabilized for sailing by the addition of buoyant floats on each side. See Sailing Rigs For Kayaks & Canoes. One French designer has made prototypes of his Windyak, a mini trimaran which is basically a kayak with a sail and outrigged floats. He says it can be paddled without removing the floats. Last time we asked, it was not yet in production. http://frederic.jouffroy.free.fr

There are some very cute micro-micro-trimarans only 9 feet 10 in long which race in the Washington/Oregon area as the International Three Meter class. One model is John Marples' Harbor Racer. They don't claim to be especially seaworthy, just fun. www.nwmultihull.org

There are some very cute micro-micro-trimarans only 9 feet 10 in long which race in the Washington/Oregon area as the International Three Meter class. One model is John Marples' Harbor Racer. They don't claim to be especially seaworthy, just fun. www.nwmultihull.org

In the UK, Solway Dory make a 16-foot sailing trimaran called the Osprey (sketch on the right). It's a nice-looking boat and performs very well in good weather at sea.

Several big manufacturers offer seaworthy 16 foot micro-multihulls with main hulls which look like kayaks but can't easily be paddled if the wind dies. There is the Windrider, made in polyethylene to a design by "Trimaran" Jim Brown. The high-sided main hull would keep you fairly dry but comes nearly up to your armpits, and the boat weighs 250 lbs. www.windrider.com There is also the Adventure Island from Hobie, which is basically a polyethylene sit-on-top kayak with two long ama. The outrigger arms get in the way of a paddle, and the boat is fitted with Hobie's pedal-operated Mirage flipper system instead. www.hobiecat.com

A proa can be described as two-thirds of a trimaran or as a sailing outrigger canoe with a single ama. Proas capsize more easily than catamarans or trimarans but if a small proa does turn over, it can be righted. Getting even a small cat or tri back on its feet again may take outside help.

A proa can be described as two-thirds of a trimaran or as a sailing outrigger canoe with a single ama. Proas capsize more easily than catamarans or trimarans but if a small proa does turn over, it can be righted. Getting even a small cat or tri back on its feet again may take outside help.

If a proa has its mast on the downwind hull, the ama may leave the water when there's a strong gust of wind. This is the flying proa, the traditional Pacific proa. If the mast is on the upwind hull as favored by a handful of 20th century designers, you have an Atlantic proa like the beautiful racing yacht Cheers designed by Dick Newick. It came third in the 1968 Observer Single-Handed Transatlantic Race (OSTAR) despite being nearly the smallest, lightest boat in the race.

Traditional Polynesian proas don't have a rudder on the stern. In fact they don't have a stern, because both ends of the hulls are identical and the boat is just as happy to go forwards as backwards. When another sailing boat would tack to go upwind, a traditional proa "shunts" instead. This means stopping, adjusting the sail to point the other way, and setting off in the opposite direction. Back becomes front. The Polynesian crab claw rig shown in the photo does it easily.

Traditional Polynesian proas don't have a rudder on the stern. In fact they don't have a stern, because both ends of the hulls are identical and the boat is just as happy to go forwards as backwards. When another sailing boat would tack to go upwind, a traditional proa "shunts" instead. This means stopping, adjusting the sail to point the other way, and setting off in the opposite direction. Back becomes front. The Polynesian crab claw rig shown in the photo does it easily.

The crab claw rig isn't just for proas. It suits most small boats that go to sea. The mast is very short. The long spars come down when you drop the sail. The sail can be cut completely flat, with no camber, so it could be made of a single sheet of fabric with no seams. All modern racing sailboats have variants on the tall triangular mainsail known as the Bermudan or Marconi rig. When properly set, a crab claw rig is more effective except directly to windward, and even then it beats most other sail rigs. See the WoodenBoat article Sail & Hull Performance by Colin Palmer, issue 92, January/February 1990. It's based on research by AC Marchaj, author of The Aero-Hydrodynamics of Sailing, who carried out wind tunnel tests with an Overseas Development Agency research program managed by fisheries consultants MacAlister Elliott & Partners. Tony Marchaj wrote in more detail in Practical Boat Owner, but we haven't seen those articles.

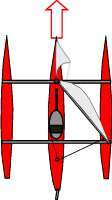

Some small proas do have a stern and a rudder, and they sail exactly like any sailing dinghy. They're called Malibu outriggers, sailing outrigger canoes or tacking outriggers. To go upwind they zig-zag in a series of "tacks", now pointing to the right of the wind, now tacking so that they point to the left of the wind. On one tack the ama is downwind, and the buoyancy of the ama keeps the boat upright. On the other tack, the ama is on the upwind side and its weight plus the weight of the crew keeps the boat upright by acting as a counterbalance to the wind in the sail. For a very nice small example, see the Dragonfly design by Chris White (illustration at left). No doubt he still sells the plans for home builders, but his website now covers only his big boats. For another illustration see www.boat-links.com/images/proapix/Dragonfly.gif

Some small proas do have a stern and a rudder, and they sail exactly like any sailing dinghy. They're called Malibu outriggers, sailing outrigger canoes or tacking outriggers. To go upwind they zig-zag in a series of "tacks", now pointing to the right of the wind, now tacking so that they point to the left of the wind. On one tack the ama is downwind, and the buoyancy of the ama keeps the boat upright. On the other tack, the ama is on the upwind side and its weight plus the weight of the crew keeps the boat upright by acting as a counterbalance to the wind in the sail. For a very nice small example, see the Dragonfly design by Chris White (illustration at left). No doubt he still sells the plans for home builders, but his website now covers only his big boats. For another illustration see www.boat-links.com/images/proapix/Dragonfly.gif

For other lovely small examples, see the Ulua and T2 designed by Gary Dierking at https://outriggersailingcanoes.blogspot.com/

A few multihulls are stabilized in motion not by the weight of the crew or the buoyancy of the ama but by one or two surface-piercing hydrofoils. Invented in America by Edmond Bruce in the mid-1960s, a Bruce foil looks very much like the daggerboard from a small sailing dinghy but it's set at an angle so it works like an underwater wing. They're not much used in commercially-made boats but a lot of people have experimented with them in fast multihull yachts.

While a boat is sailing, the wind in the sail tries to push it over sideways. If you get the geometry right, a Bruce foil on the downwind side resists this like a wing, "flying" in the water and producing lift. The foil on the upwind side does the opposite, creating a force which sucks it down into the water. The result is that the boat sails along rock-solid upright, without any need for the sailor to move his or her weight around as a counterbalance. In fact most foil-stabilized boats have amas too, or at least some sort of buoyancy on the end of the crossbeam, because a foil only works if the boat is moving. If the boat is stationary, a foil is just a plank.

While a boat is sailing, the wind in the sail tries to push it over sideways. If you get the geometry right, a Bruce foil on the downwind side resists this like a wing, "flying" in the water and producing lift. The foil on the upwind side does the opposite, creating a force which sucks it down into the water. The result is that the boat sails along rock-solid upright, without any need for the sailor to move his or her weight around as a counterbalance. In fact most foil-stabilized boats have amas too, or at least some sort of buoyancy on the end of the crossbeam, because a foil only works if the boat is moving. If the boat is stationary, a foil is just a plank.

A few racing sailors use hydrofoils not just to stabilize their boats but to lift them right out of the water. There's even a commercial version, the Windrider Rave at www.windrider.com, but we're thinking about the relatively gentle version, foils for stabilization. An elegant and attractive foil-stabilized boat was the SkiSail, designed by David Chinery (illustration at right). This had a hull resembling an 18 foot racing ski with the stern removed to take a rudder, stabilized by small buoyant foils on the ends of a fiberglass outrigger, powered by a windsurfer rig. It deserved to be a commercial success, but wasn't. For a temporary Bruce foil stabilizer which can be strapped to any kayak, see the K-Wing at Sailing A Kayak.

A few racing sailors use hydrofoils not just to stabilize their boats but to lift them right out of the water. There's even a commercial version, the Windrider Rave at www.windrider.com, but we're thinking about the relatively gentle version, foils for stabilization. An elegant and attractive foil-stabilized boat was the SkiSail, designed by David Chinery (illustration at right). This had a hull resembling an 18 foot racing ski with the stern removed to take a rudder, stabilized by small buoyant foils on the ends of a fiberglass outrigger, powered by a windsurfer rig. It deserved to be a commercial success, but wasn't. For a temporary Bruce foil stabilizer which can be strapped to any kayak, see the K-Wing at Sailing A Kayak.

There have been at least two small foil-stabilized boats on the market recently. The Raptor 16 by John Slattebo was a successful design until it fell victim to the recession. At the time of writing it's out of production, but see www.raptor-uk.net.

Until 2010 the Triak from www.triaksports.com. was fitted with very small foils to keep its outrigger floats up off the surface, but there's no sign of them in today's model.

Until 2010 the Triak from www.triaksports.com. was fitted with very small foils to keep its outrigger floats up off the surface, but there's no sign of them in today's model.

At first glance the Triak (red sketch) looks very similar to the SkiSail, with a main hull like an 18 foot 6 in racing kayak, stabilized by trimaran-type floats on the end of a fiberglass outrigger beam. The sailing rig is sophisticated and complicated.

At first glance the Triak (red sketch) looks very similar to the SkiSail, with a main hull like an 18 foot 6 in racing kayak, stabilized by trimaran-type floats on the end of a fiberglass outrigger beam. The sailing rig is sophisticated and complicated.

The Triak really scores over the SkiSail because the crossbeam leaves space to use a kayak paddle. So does a similar sailing-paddling kayak, the Viroga (orange sketch) from www.viroga.com

Yachts & sea kayaks

There's nothing quite like entering a new harbor after a long voyage under sail, or sitting in the cockpit of your moored yacht in some quiet estuary, watching the sun set. Yachts are great, but they have three disadvantages. They are expensive, they break if you hit something, and they're not very portable.

There's nothing quite like entering a new harbor after a long voyage under sail, or sitting in the cockpit of your moored yacht in some quiet estuary, watching the sun set. Yachts are great, but they have three disadvantages. They are expensive, they break if you hit something, and they're not very portable.

It is a major undertaking to get even a trailer-sailer onto the highway, so for weekend sailing, yachts are usually confined to a 50-mile radius from their home port. That's fine if you race for a few hours and then head for the yacht club bar, but it gets a bit repetitive if you prefer cruising.

I love using and looking at boats with paddles, oars and sails. That's me above, helming LeGrandBois from Exmouth over to France, and below you can see my left foot enjoying the sun in the Channel Islands. I've noticed that most yachts and dayboats go sailing less than two days per year. That doesn't sound like much use for something that costs as much as a car or a house and has a twenty-year life.

Yachtsmen buy the dream (and it's not cheap) but life gets in the way. Here's a quote from Dan Segal. He was editor of The Yacht magazine and the Small Boat Journal, so they don't come much saltier. Writing in WoodenBoat magazine he said: "Cruising boats are really more trouble than they're worth... between watering, provisioning, fueling, pumping the head, logistics, transportation for the crew, getting everything aboard, airing out, stowing, scrubbing down, not to mention the maintenance, repairs, worry and who knows what else, most cruising-boat owners are exhausted before they ever leave the mooring. It's easier to stay home and watch the baseball game".

And in case you think Dan was probably just suffering from indigestion that week, here's a quote from a British yachtsman. Nigel Irens has designed serious powerboats including Ilan Voyager, but he's really a sailor and designer of sailing yachts. He designed some of the fastest racing sailboats ever built, including Formule Tag/Enza, Apricot, Fleury Michon VIII and Fleury Michon IX, Ellen McArthur's 2004 trimaran B&Q/Castorama, Sodeb'o and IDEC 2. He says "the richer you are, the bigger your boat, the more it draws, and the fewer places it can take you. I know of yachts moored in some of the most beautiful estuaries...and all their owners ever see is the same old stretch of coastline outside the river's entrance. There's a whole world upstream that they've never...dreamed of".

Maybe that's a good reason for taking a sea kayak or two aboard your yacht. Some of the world's most famous yachtsmen and yacht designers spend more time in kayaks than they do sailing. The list includes designer L Francis Herreshoff, who called his a double-paddle canoe, and Herreshoff's draftsman Norman L Skene, author of Skene's Elements of Yacht Design. Trimaran designer Dick Newick said that his "dream fleet" of boats under 25 feet long would be his own 23 foot 6 in Tremolino trimaran plus a 16 foot kayak kept at Kittery Point, Maine. Cruising monohull designer Phil Bolger said that of all the boats he'd ever owned, whether power, sail, oar or paddle, and whether for cruising, daysailing, racing or work, his kayak always got more use than anything else, and yacht designer Roger Young says that his own similar design was "unquestionably ...the boat I've had more fun in than any other I've been associated with."

Sailors are understandably reluctant to get too close to headlands, reefs and islands; or to enter narrow inlets edged by ancient oaks, or sandy estuaries with their sweeping tides.

Sailors are understandably reluctant to get too close to headlands, reefs and islands; or to enter narrow inlets edged by ancient oaks, or sandy estuaries with their sweeping tides.

A yacht is usually more than 500 yards away from the coast, and on passage the land seen from the cockpit of a yacht is just a thin gray line.

Sea kayakers are usually to be found within 50 yards of the coast, looking at cliffs, towers and reefs, seaweed, waves, birds and animals.

Go to next page for:

• Sailing Rigs For Kayaks & Canoes