Here you will find an introduction to 19th century canoe sailing plus the canoe sailing chapter from the 1895 edition of the Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing. There's a separate Kayarchy chapter about modern sailing canoes for use on exposed waters.

Dixon Kemp and the Manual

Dixon Kemp was a yachting journalist and yacht designer. He designed several steam yachts but most of his designs had to sail, and sail well. Sail racing was a very competitive sport. Also, few boats at the time had engines, and radios, lifeboats and weather forecasting were almost non-existent. Here's a testament to Kemp's design skills : When Alain Gerbault wanted to sail round the world solo in 1923, he chose Kemp's Firecrest cruiser-racer.

Dixon Kemp went often to the USA to watch international yacht races and explore the racing scene. He was a founder-member of the Yacht Racing Association which became the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) but today he is probably best known for his sailing books. His Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing was a best-seller, was issued by the British Admiralty to Royal Navy ships for training purposes, and went through nine editions between 1878 and 1895. After Kemp's death in 1899 there were further editions revised by leading yacht designers in 1904 and 1913.

Back in 1878, sail cruising and racing were already very popular on both sides of the Atlantic, at all levels from weekend dinghy clubs to America's Cup yacht race fever. Boats were undergoing constant radical changes of shape as new ideas and new rating rules were tried out. Dixon Kemp was in touch with hundreds of sailors, designers and boatbuilders round the world and he documents the evolution of classic dinghies such as the Dublin Bay Water Wag and the Sydney Harbour 18 Foot Skiff. Kemp also shows "skimming dish" monohulls which look very like today's Melges scow classes or Open 60 racers, and a racing catamaran, the 32 foot John Gilpin that would not be much out of place in a multihull race today. It was an N G Herreshoff design, following on from his 25-footer Amaryllis which did 14 knots in 1875 and was immediately banned from racing against monohulls because she was too fast.

Dixon Kemp and canoe sailing

Sailing canoes were very popular during the years when Kemp wrote and updated the Manual, and he gave them a chapter to themselves with a lot of material from designer Warington Baden Powell. Sailing canoes were more affordable than yachts, often more seaworthy than dinghies, you could haul them up the beach yourself, and you could take them on holiday in a railway luggage van.

People have always put up small sails to help a canoe or kayak go downwind. The start of canoe sailing as a popular sport goes back to 1865 when a London lawyer designed a 15 foot boat for himself. John MacGregor had tried Indian canoes during a tour of the USA and Canada in 1858 but his own "Rob Roy canoe" was based on the Inuit kayak.

People have always put up small sails to help a canoe or kayak go downwind. The start of canoe sailing as a popular sport goes back to 1865 when a London lawyer designed a 15 foot boat for himself. John MacGregor had tried Indian canoes during a tour of the USA and Canada in 1858 but his own "Rob Roy canoe" was based on the Inuit kayak.

MacGregor used a double bladed paddle and put up a small sail to increase his range when the wind was behind him. He used this and later versions of his design in Europe, Scandinavia and the Middle East, and he wrote best-selling books about his adventures starting with A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe in 1866. The novelist Robert Louis Stevenson (another lawyer) paddled and sailed a Rob Roy-type canoe through Belgium and France in 1876 and wrote another best-seller about it, called An Inland Voyage.

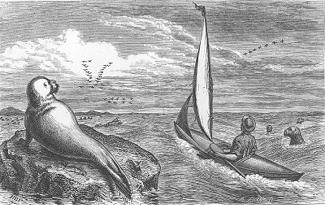

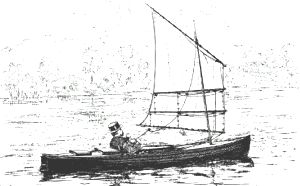

Warington Baden Powell, (yes, another lawyer) did a similar high-profile canoe trip. Here are two illustrations from his 1871 book Canoe Travelling : Log of a Cruise on the Baltic . If you want to buy a reproduction of the book, they're available from DN Goodchild's Shellbacks Library. Warington B-P was the brother of Robert Baden Powell who founded the Boy Scouts organisation. Obviously a remarkable man, he was also a Master Mariner, a lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve and the founder of the Sea Scouts.

|

|

|

Here's an affordable, portable little French canoë de mer sailing canoe from the Lexique at Le Carré des Canotiers:

Portable and affordable is good, but the early models couldn't carry much sail or make any progress upwind. Sailing canoes soon became more sophisticated.

Portable and affordable is good, but the early models couldn't carry much sail or make any progress upwind. Sailing canoes soon became more sophisticated.

On the right, also kindly provided by Le Carré des Canotiers, is a 13 foot 7 in by 31.5 inch canoë de mer sailing canoe, built by Tellier in Paris in 1887. Hmm, 1887. Elsewhere in Paris the Eiffel Tower was under construction, the Statue of Liberty had recently been shipped to New York, and Van Gogh and Seurat were painting.

On the right, also kindly provided by Le Carré des Canotiers, is a 13 foot 7 in by 31.5 inch canoë de mer sailing canoe, built by Tellier in Paris in 1887. Hmm, 1887. Elsewhere in Paris the Eiffel Tower was under construction, the Statue of Liberty had recently been shipped to New York, and Van Gogh and Seurat were painting.

And here's a picture of Siren, a US-built Nautilus sailing canoe, from John Summers' Playing With Boats. Warington Baden Powell corresponded with Dixon Kemp and designed a whole series of Nautilus boats which evolved through different editions of the Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing.

And here's a picture of Siren, a US-built Nautilus sailing canoe, from John Summers' Playing With Boats. Warington Baden Powell corresponded with Dixon Kemp and designed a whole series of Nautilus boats which evolved through different editions of the Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing.

Masts got longer, sails got bigger, sailing canoes got heavier and more sophisticated. For a time, canoes could be both paddled and sailed without the canoeist being an acrobat or spending a fortune. The sailor still sat inside the boat, only sitting up on deck when sailing close to the wind. In the words of Dixon Kemp "paddling demands an upright position of the man's body, but sailing equally demands a lowering of the weights, and consequently a reclining position .... when running dead before a strong wind ... comfort, combined with safety ... will be obtained ... by lying back, and firmly wedging one's shoulders between the two sides of the after well-coamings." This is an 1886 one-person Nautilus, 14 feet long and 33 inches wide:

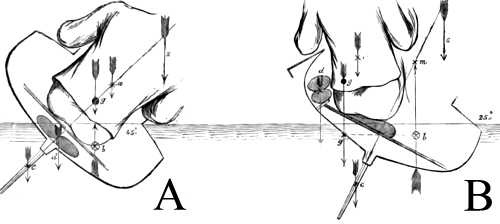

As a yacht designer, Dixon Kemp was able to explain the technical side of sailing stability for this sort of canoe. In the two cross-sections below, the markings show the centres of gravity, centre of buoyancy and metacentre.

The picture above left shows a basic sailing canoe like the original Rob Roy or an early Nautilus design, with a fixed seat and some ballast in the form of lead shot carried in bags under the seat, which Dixon Kemp didn't think was an effective place for it. In windy conditions this design is uncomfortable, wet and not stable enough to carry much sail. Above right is a more complicated arrangement with hinged deck flaps so the sailor can shift his weight to windward, and move the two bags of lead shot to windward too. Kemp said this was the way to sail a sit-in canoe efficiently. He didn't think much of carrying bags of lead shot under the seat by way of internal ballast. In a sailing canoe, unless a sailor was willing to bolt a lead ballast keel underneath the bottom,"the ballast cannot be got low enough ... and it is becoming more and more acknowledged that, for canoe sailing, a pound of shifted ballast is more effectual than ten pounds of weight stowed beneath the floor boards."

It's relaxing and fun to sail while sitting inside the canoe, facing forward. It's dry if the weather's reasonable, and it gives you armchair comfort. If you want to go to windward on a day of strong or gusty wind, you can drop the sailing rig and get out your paddle. This gentle sort of sailing has made a comeback recently, and Kayarchy has a chapter about it called Sailing Canoes for Exposed Waters.

Of course most sailors want more power, especially to go to windward. Whether in the 19th century or today, if you want to sail a canoe to windward, especially on a windy day, you need to do something to resist the wind pressing on your sail which wants to capsize you. In a light and simple sailing canoe you can sit up on the side deck and lean your body weight to windward. It's fun but you'll get very wet and maybe go for a swim.

Of course most sailors want more power, especially to go to windward. Whether in the 19th century or today, if you want to sail a canoe to windward, especially on a windy day, you need to do something to resist the wind pressing on your sail which wants to capsize you. In a light and simple sailing canoe you can sit up on the side deck and lean your body weight to windward. It's fun but you'll get very wet and maybe go for a swim.

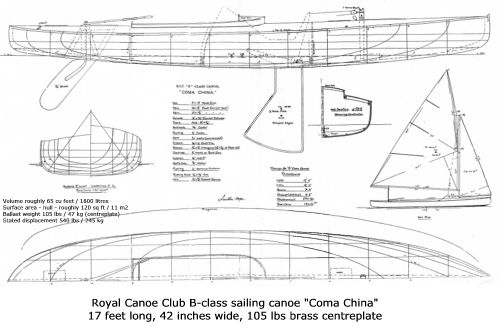

Ironically, the thing that killed off the 19th century sailing canoe was a move away from these simple designs in search of more sail power. During Dixon Kemp's time with the Manual, canoe designs changed until eventually most sailing canoes were one of two extreme kinds, either expensive miniature yachts like Linton Hope's Coma China design, fitted with a complex sailing rig and an external ballast keel to keep it upright while sailing along the coast, or pure racing machines like the 16-30 or the IC10 where the sailor sits out to windward on a sliding seat. A few more words from Dixon Kemp: "Thus far we have looked at the sail carrying power of canoes where the skipper sits below deck, but a far more powerful mode of balance is that obtained by the 'crew' sitting on the side deck ... in America this position of power has been extended by the use of a sliding seat board which is shoved out to windward, and then the 'crew' coils himself up on the outer end of the board."

Dixon Kemp's Canoe Sailing chapter

Below you will find links to the original pages of the Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing for 1895, and here's a link to the Yachtsport Archiv's reproduction of the canoeing chapter from the Seglers Handbuch (1897, Georg Belitz) with similar information in German.