• Is it a whitewater day?

• The shape of fast water:

- eddies

- standing waves

- holes

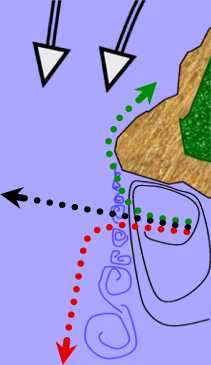

Example of a hole

The photo above shows the deep hole which appears next to Ramsey Island at some stages of the tide.

Ramsey is off the south west tip of Pembrokeshire, in Wales. The channel between the island and the mainland is called Ramsey Sound. The B-tches [to which we're giving a slightly euphemistic name because we don't want to be blacklisted by Google] is a line of little islands which goes halfway across the Sound. At unusually low tides, you can walk along the chain of islands and hardly get your feet wet. A very fast tidal stream runs through Ramsey Sound for several hours every day, creating conditions which are popular with playboaters. There are often surfable standing waves between the little islands.

In the chapter on sea kayak navigation you will find a chart extract of the area. This is a small scale chart, only 1:75,000, so the B-tches are not named but they are shown as a green finger sticking out from the middle of the east side of Ramsey.

They are 350 yards wide so you'd need a magnifying glass to see a kayak in this photo, which was taken from 130 feet up on Ramsey looking east. Note the two-masted sailing yacht in the background. There are lots of standing waves, several of which are surfable. Downstream of each little island is a pair of large back eddies, separated from the main current by a turbulent white eddyline.

The B-tches can be just terrifying at peak flow on spring tides if there is wind and a powerful swell. This photo was taken on a good play day.

The constriction caused by the islands makes the tidal stream speed up a little. Next to Ramsey Island the current pours over a ledge of rock and descends in a 30 degree ramp of fast water. It often goes down about 3 feet, creating a hole which has a stopper wave as its downstream edge.

Playboats can enter the hole from above, below or to the side and play in various ways, surfing the wave and doing tricks. At one time there was an annual playboat rodeo on the B-tches with cameras and prizes. It has its own website courtesy of Matt O'Brien, with great photos and tidal stream information. We're not going to give a link to it [Google paranoia again] but you will go straight there if you do an Internet search on "matt o'brien" white water play spot ramsey sound. See also the comments on Horse Rock at Large Back Eddies & Whirlpools.

Holes & sea kayaks

You can take a sea kayak down through most parts of the B-tches with very little fuss. A confident kayaker will try breaking out into one of the back eddies downstream of the islands so as to ferry glide onto one of the standing waves for a little surfing.

Even the hole does not, on most days and most states of the tide, present a real obstacle. If you do see a ramp of smooth water descending ahead of you, with a wall of white water waiting for you at the bottom, you will definitely paddle as hard as you can. Your momentum will help the long hull of your kayak cut through the stopper like a hot knife through butter. If you keep paddling hard even when the wall hits you in the chest and face, generally you find yourself down-tide of the hole and still upright.

Approaching the hole from downstream is a different matter and takes thought. It is not generally worth dropping a sea kayak into a hole, because there is not much you can do with it in there and there's a significant risk that it will get damaged.

If you take a long kayak into a hole from directly downstream, there will come a point when the front of it enters the ramp of fast water flowing over the ledge. It will then be forced under water until it hits the rock ledge (ouch). In a medium-sized hole the water may be deep enough for the entire kayak to go vertical (an ender) and fall over forwards (forward loop). This is fine as long as the ends of your kayak don't hit anything solid, and as long as you are able to roll in the very fast, turbulent water downstream. In a few holes, the water will turn your kayak sideways and hold you.

Stuck sideways in a hole?

Any stopper likes to turn kayaks sideways and make them drop into the bottom of the slot. If the slot is a foot deep you may find it hard to paddle out again. If it's 3 feet deep, you won't be able to see out and the noise and turbulence will be shocking.

The moment you arrive in the bottom of any slot you must raise the upstream edge of your kayak. Edging your kayak downstream is crucial because otherwise the water rushing under the bottom of your kayak will instantly capsize you upstream. In other words, keep that upstream gunwale raised so the water cannot grab hold of it and flip you into an upstream capsize.

Keep your downstream paddle blade on top of the breaking wave. See the paddle brace strokes at Keeping A Moving Kayak Upright. In the middle of the wave, the water is flowing vertically upwards so you may be able to support yourself with no more than a low brace. If things are really turbulent, try a sculling brace or high recovery strokes - whatever works!

Probably the hole will release you after a few seconds. If not, work your way backwards or forwards to a low point or to the end of the wave. If you capsize and come out of your kayak, a hole at sea will almost certainly spit you and your kayak out straight away. So make sure your friends are ready to chase after you.

Dangerous holes

A dangerous hole may hold onto you even if you come out of your kayak. These are not common on whitewater rivers until human engineers get involved, bless 'em, and they are extremely rare at sea.

We know of only one at sea in Britain, at the north end of the tunnel under the Stanley Embankment which takes the A5 from Anglesey to Holyhead. Vacationers heading for the ferry may be only yards above a kayaking drama. It's a playwave for some, but given the right tidal conditions it can be nasty on the ebb. In Snowdonia White Water, Sea & Surf (Cicerone Press, 1986) Terry Storry said "this powerful hidden stopper, which is closed off at both ends, has been known to back-loop sea kayaks, and will be the death of someone some day".

It can be difficult at first glance to tell the difference between a friendly standing wave and a dangerous hole. They both have a ramp of smooth water flowing down to a stationary wave. They may both have a breaking crest, and a tail of turbulent water extending downstream from the crest. The clearest sign of a bad hole is that the turbulent water on the surface downstream of the crest is flowing upstream in a wide band across your route (towback).

Other signs of a dangerous hole include one or more of the following:

• A vertical or steep ramp of smooth water pouring down into the hole from upstream. Water rushing down a slope of 30 degrees or more can create a very adhesive stopper even if the slot is only 8 inches deep. And the water crashing onto your deck will make it hard to stay upright.

• The middle of the stopper wave is further downstream, or further down vertically, than the ends. If you get stuck sideways you will want to paddle towards one of the ends, and it's hard to paddle uphill.

• A continuous, regular profile from one side of the channel to the other. This is the sign of an artificial ledge under the water - natural ledges nearly always have a slightly irregular profile which gives the water, and a kayaker, at least one easy point to leave the hole and go on downstream.

• Rocks or walls which close off the wave at both ends. Again, usually a sign that human engineers have been there.

Like we said, we give some pointers but please don't approach a hole unless you have the necessary experience. OK, that's more than enough about the unpleasant side of fast water.

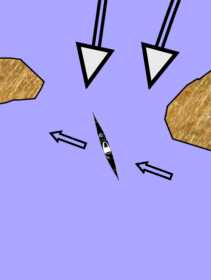

If you enter a fast stream of water at a fine angle, with your kayak pointing almost directly upstream, the current will not grab the front of your kayak or take you downstream. If your kayak is at an angle of 10 to 30 degrees to the fast stream it will carry you rapidly across to the other side. River ferries use the power of the current in this way, so it's called ferrying or the ferry glide.

If you enter a fast stream of water at a fine angle, with your kayak pointing almost directly upstream, the current will not grab the front of your kayak or take you downstream. If your kayak is at an angle of 10 to 30 degrees to the fast stream it will carry you rapidly across to the other side. River ferries use the power of the current in this way, so it's called ferrying or the ferry glide.